Alcohol's Metabolic Priority and Energy Balance

Understanding how ethanol influences substrate oxidation and overall energy metabolism through evidence-based research

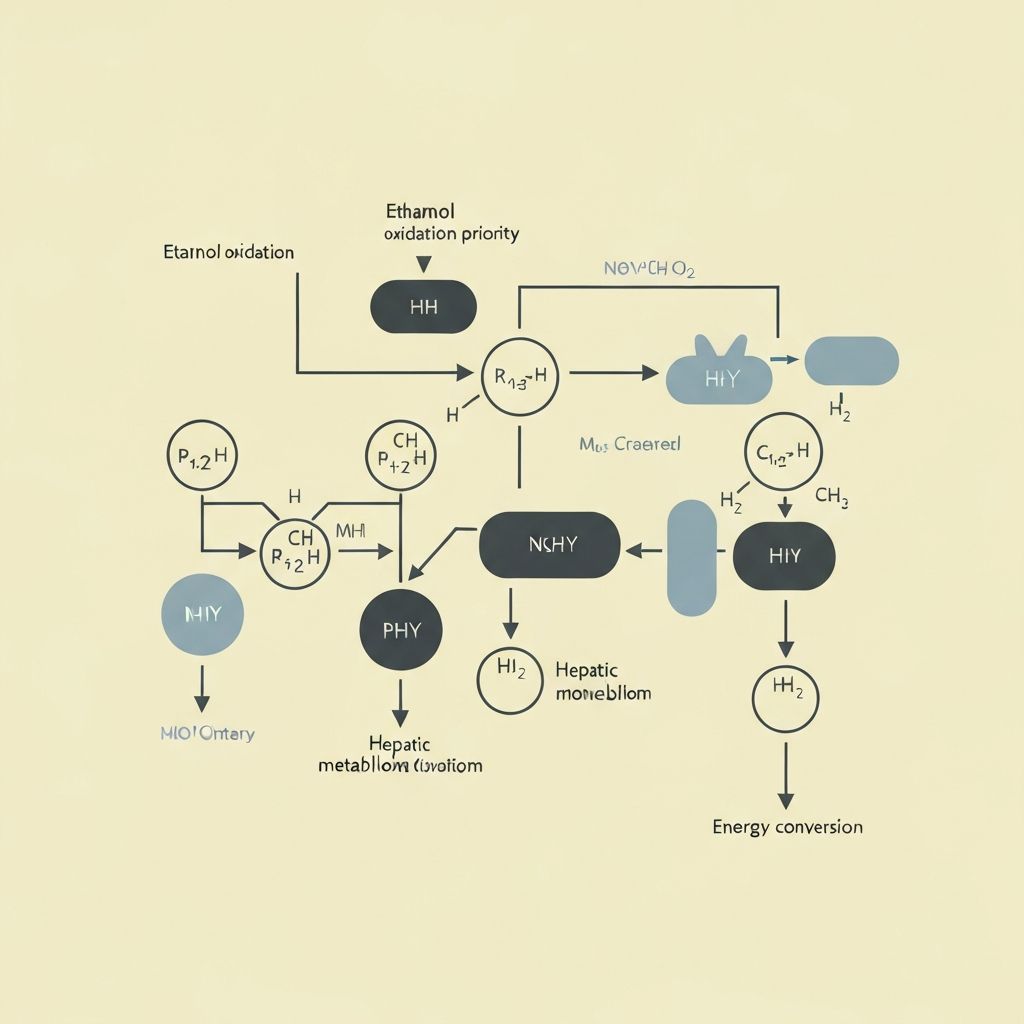

Alcohol as a Priority Substrate

Ethanol contains 7 kilocalories per gram, making it a significant source of energy. Once consumed, the liver prioritizes its oxidation over other macronutrients, treating alcohol as the primary substrate for energy production.

This metabolic hierarchy reflects the body's attempt to eliminate a toxic compound as quickly as possible. The oxidation of ethanol occurs through a multi-step enzymatic process involving alcohol dehydrogenase and aldehyde dehydrogenase, generating NADH and contributing to the overall energy budget.

Inhibition of Fat Oxidation

A key consequence of alcohol's metabolic priority is the suppression of fat oxidation. When ethanol is present, the body shifts focus away from breaking down dietary and stored fats. This occurs because the acetyl-CoA produced from alcohol metabolism, combined with elevated NADH levels, inhibits the enzymatic pathways responsible for fat breakdown.

Research observations indicate that during periods of alcohol consumption, rates of fat oxidation decline compared to baseline conditions. This does not mean fat stored in the body cannot be mobilized later; rather, it reflects an acute shift in metabolic priorities that can influence the overall energy balance during and shortly after alcohol intake.

The magnitude of this suppression varies with alcohol dose and individual metabolic factors, though the general pattern is consistent across studied populations.

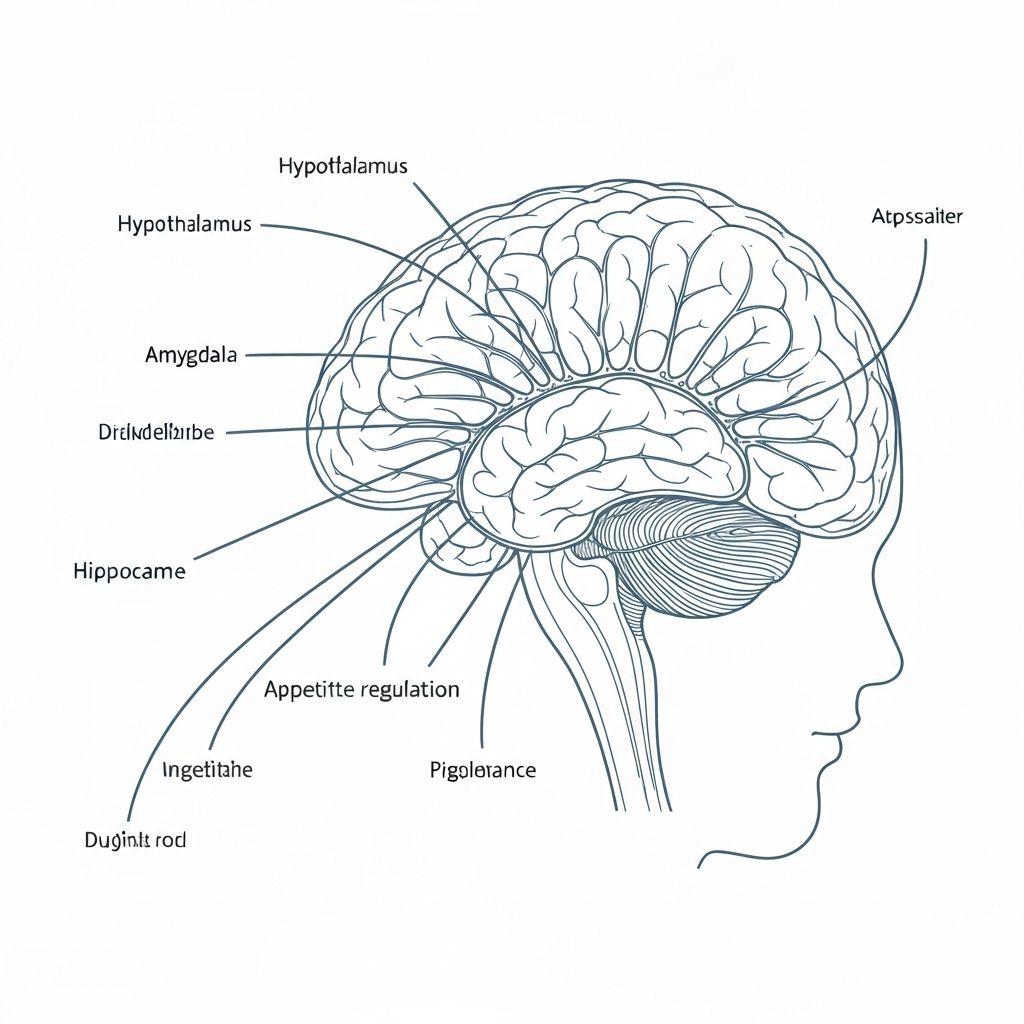

Appetite and Intake Disinhibition

Epidemiological and experimental studies have documented a phenomenon termed alcohol-induced disinhibition. This describes increased food intake in the presence of alcohol, often exceeding what would be expected to compensate for the energy provided by the beverage.

Mechanisms underlying this effect include altered signaling from appetite-regulating hormones such as leptin, as well as changes in satiety perception. Alcohol can enhance food palatability perception and reduce inhibitory control over eating behavior, leading to ad libitum consumption patterns that frequently result in a net energy surplus.

Hormonal Alterations from Alcohol

Alcohol consumption triggers multiple endocrine responses. Acute alcohol intake is associated with reduced leptin levels, a hormone signaling energy sufficiency to the brain. Simultaneously, ethanol can elevate cortisol, particularly during chronic consumption, which may promote preferential energy storage in certain tissue types.

Additionally, alcohol affects insulin secretion and sensitivity, though responses vary depending on dose, timing, and nutritional context. Changes in testosterone and growth hormone levels have also been observed, though these effects are typically transient with moderate consumption and more pronounced with heavy intake.

These hormonal shifts collectively influence appetite perception, energy expenditure, and substrate utilization, contributing to the observed associations between alcohol consumption and changes in body composition.

Energy Contribution of Typical UK Drinks

The following table provides a reference for the caloric and unit content of commonly consumed alcoholic beverages in the United Kingdom:

| Beverage | Typical Serving | Units of Alcohol | Approximate kcal |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pint of Bitter or Lager (4.5% ABV) | 568 ml | 2.4 | 180–210 |

| Glass of Red Wine (13% ABV) | 150 ml | 1.9 | 120–135 |

| Gin & Tonic (40% ABV gin, 100 ml + mixer) | 180 ml total | 3.2 | 140–180 |

| Glass of White Wine (12% ABV) | 150 ml | 1.8 | 115–130 |

| Shot of Whisky (40% ABV) | 25 ml | 1.0 | 55–65 |

Mixers and Compounded Energy Load

The addition of sugary or calorically dense mixers significantly increases the total energy contribution of an alcoholic drink. Soft drinks, juices, and traditional tonics can add 50–150 calories per serving.

Mixers containing high-fructose corn syrup or added sugars also contribute to the overall glycemic load and may amplify some of the appetite-related effects observed with alcohol. The combination of ethanol and rapid-absorbing carbohydrates may particularly enhance the disinhibition of eating behavior.

In contrast, alcohol mixed with calorie-free beverages avoids this compounding effect, though the metabolic priority and hormonal effects of the ethanol itself remain unchanged.

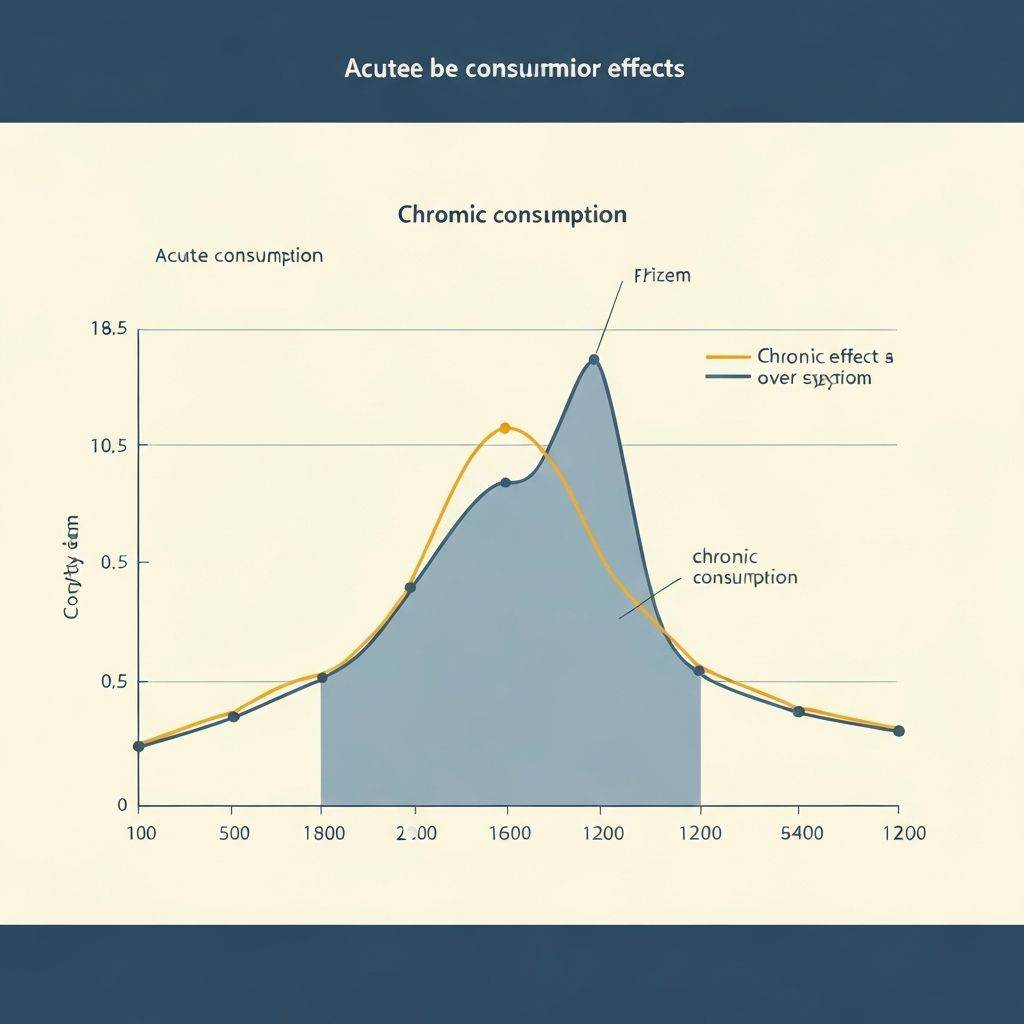

Acute vs Chronic Consumption Effects

The metabolic consequences of alcohol differ somewhat between single-occasion consumption and habitual intake. Acute consumption of moderate amounts produces the shifts in substrate oxidation, leptin suppression, and disinhibition described above, typically resolving within hours to a day as the alcohol is metabolized.

Chronic consumption, defined as regular intake over weeks or months, can produce sustained hormonal adaptations and may contribute to altered energy balance regulation at a systems level. Liver function, metabolic flexibility, and the compensatory responses to nutrient intake may all be influenced by habitual alcohol use.

The body's capacity to adapt to chronic alcohol exposure creates heterogeneity in observed outcomes: some individuals show more pronounced weight changes than others in response to similar patterns of alcohol consumption, reflecting differences in baseline metabolism, diet composition, physical activity, and individual hormonal sensitivity.

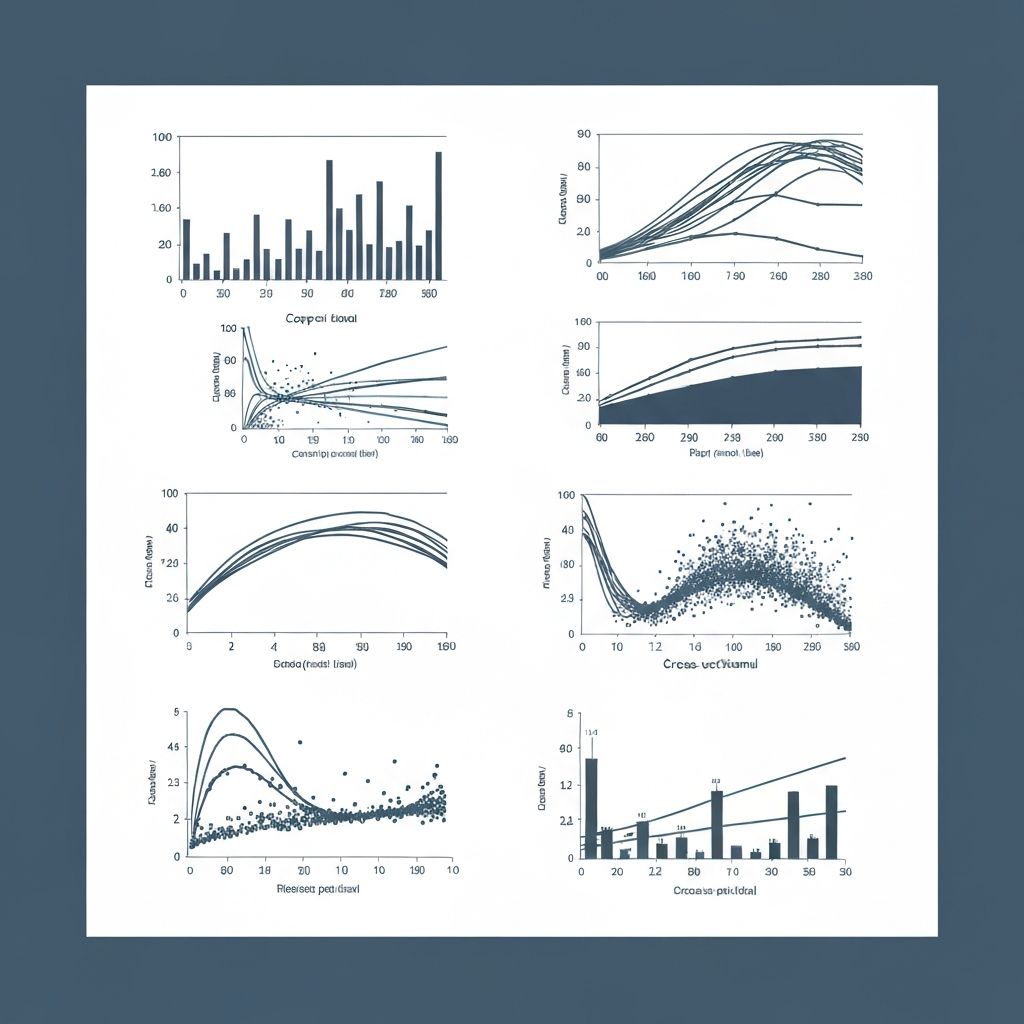

Observational Data on Alcohol and Weight

Population-level research, including cohort and cross-sectional studies, has identified statistical associations between alcohol consumption patterns and body weight changes. These studies vary in findings depending on consumption level, study design, and the population examined.

Some research indicates that moderate to heavy alcohol consumption is associated with higher average body weight, particularly when consumed in combination with high-calorie food patterns. Other studies find weaker or curvilinear relationships, with minimal weight differences at lower consumption levels.

It is important to emphasize that observational associations do not establish causation. These studies cannot definitively prove that alcohol consumption itself causes weight gain; factors such as overall diet quality, physical activity, sleep patterns, and metabolic health status all interact to influence outcomes. Additionally, reverse causation and confounding variables complicate the interpretation of such data.

The evidence supports the biological plausibility of an effect, but individual responses remain highly variable.

Explore Alcohol and Energy Balance Research

The following articles provide detailed exploration of specific aspects of alcohol metabolism and energy balance:

Ethanol Oxidation Priority in Human Metabolism

Biochemical pathways and enzymatic mechanisms behind the preferential oxidation of ethanol.

Read the explanationAlcohol and Suppression of Fat Oxidation: Acute Effects

Research data on short-term changes in lipid oxidation during and after alcohol consumption.

Learn moreAlcohol-Induced Appetite Disinhibition

Intake compensation studies and mechanisms of increased ad libitum food consumption.

Explore the researchEndocrine Responses to Alcohol

Hormonal changes including leptin, cortisol, insulin, and growth hormone effects.

Continue readingCaloric Density of Common UK Beverages

Detailed profiles of energy and unit content for popular alcoholic drinks.

View profilesAlcohol Consumption Patterns and Body Weight

Observational evidence from cohort and cross-sectional studies on associations with weight.

Examine evidenceFrequently Asked Questions

Yes. Ethanol provides 7 kilocalories per gram and is oxidized for energy. However, unlike macronutrients, alcohol is not stored as such; it must be metabolized immediately. Its high metabolic priority influences substrate utilization patterns.

The liver prioritizes ethanol oxidation due to its toxic potential. The metabolic byproducts—particularly NADH—alter the cellular environment in ways that inhibit fatty acid oxidation. This is a physiological adaptation, not a deliberate storage mechanism.

From an energetic standpoint, yes. If the total caloric intake (including alcohol) matches energy expenditure, weight maintenance is theoretically possible. However, the appetite-disinhibiting effects of alcohol often lead to overconsumption of food, making consistent energy balance more challenging in practice for many people.

Population studies show variable associations between alcohol consumption and weight gain. Some find statistically significant links, particularly with heavier consumption; others find minimal effects at lower levels. Individual responses depend on overall diet, activity, genetics, and other lifestyle factors.

Alcohol alters leptin, cortisol, and insulin levels acutely. These changes influence appetite perception, energy expenditure, and substrate preference. Chronic consumption can produce sustained endocrine adaptations, though the magnitude varies greatly among individuals.

Understanding Alcohol's Role in Energy Regulation

The relationship between alcohol consumption and energy balance is multifaceted, involving substrate oxidation, hormonal signaling, and behavioral factors. Rather than viewing alcohol through a simplistic lens of "good" or "bad," evidence suggests a nuanced picture: ethanol's metabolic priority, combined with its appetite-related effects and the potential added calories from mixers, creates a context in which maintaining energy balance requires awareness and intentionality.

This resource aims to clarify the physiological mechanisms at play, enabling informed understanding of how alcohol interacts with the body's energy systems. We invite you to explore the detailed research articles linked above for deeper examination of specific topics.

Educational content only. No promises of outcomes.